By Tom Perry and Imad Creidi

BEIRUT (Reuters) – Looking back on his childhood in the newly declared state of Lebanon nearly a century ago, Salah Tizani says the country was set on course for calamity from the start by colonial powers and sectarian overlords.

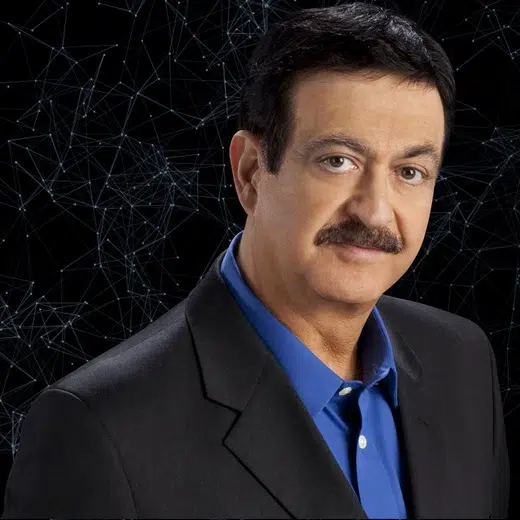

Tizani, better known in Lebanon as Abou Salim, was one of Lebanon’s first TV celebrities. He shot to fame in the 1960s with a weekly comedy show that offered a political and social critique of the nascent state.

Now aged 92, he lucidly traces the crises that have beset Lebanon – wars, invasions, assassinations and, most recently, a devastating chemicals explosion – back to the days when France carved its borders out of the Ottoman Empire in 1920 and sectarian politicians known as “the zuama” emerged as its masters.

“The mistake that nobody was aware of is that people went to bed one day thinking they were Syrians or Ottomans, let’s say, and the next day they woke up to find themselves in the Lebanese state,” Tizani said. “Lebanon was just thrown together.”

Lebanon’s latest ordeal, the Aug. 4 Beirut port explosion that killed some 180 people, injured 6,000 and devastated a swathe of the city, has triggered new reflection on its troubled history and deepened worry for the future.

For many, the catastrophe is a continuation of the past, caused in one way or another by the same sectarian elite that has led the country from crisis to crisis since its inception, putting factions and self-interest ahead of state and nation.

And it comes amid economic upheaval. An unprecedented financial meltdown has devastated the economy, fuelling poverty and a new wave of emigration from a country whose heyday in the 1960s is a distant memory.

The blast also presages a historic milestone: Sept. 1 is the centenary of the establishment of the State of Greater Lebanon, proclaimed by France in an imperial carve-up with Britain after World War One.

For Lebanon’s biggest Christian community, the Maronites, the proclamation of Greater Lebanon by French General Henri Gouraud was a welcome step towards independence.

But many Muslims who found themselves cut off from Syria and Palestine were dismayed by the new borders. Growing up in the northern city of Tripoli, Tizani saw the divisions first hand.

As a young boy, he remembers being ordered home by the police to be registered in a census in 1932, the last Lebanon conducted. His neighbours refused to take part.

“They told them ‘we don’t want to be Lebanese’,” he said.

Tizani can still recite the Turkish oath of allegiance to the Sultan, as taught to his father under Ottoman rule. He can sing La Marseillaise, taught to him by the French, from start to finish. But he freely admits to not knowing all of Lebanon’s national anthem. Nobody spoke about patriotism.

“The country moved ahead on the basis we were a unified nation but without internal foundations. Lebanon was made superficially, and it continued superficially.”

From the earliest days, people were forced into the arms of politicians of one sectarian stripe or another if they needed a job, to get their children into school, or if they ran into trouble with the law.

“Our curse is our zuama,” Tizani said.

POINTING TO CATASTROPHE

When Lebanon declared independence in 1943, the French tried to thwart the move by incarcerating its new government, provoking an uprising that proved to be a rare moment of national unity.

Under Lebanon’s National Pact, it was agreed the president must be a Maronite, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim and the speaker of parliament a Shi’ite Muslim.

The post-independence years brought signs of promise.

Women gained suffrage in 1952. Salim Haidar, a minister at the time, took pride in the fact that Lebanon was only a few years behind France in granting women the right to vote, his son, Hayyan, recalls.

Salim Haidar, with a doctorate from the Sorbonne, drafted Lebanon’s first anti-corruption law in 1953.

“This was the mentality … that Lebanon is really leading the way, even in the legal and constitutional matters. But then he didn’t know that all of these laws that he worked on would not be properly applied, or would not be applied at all, like the anti-corruption law,” Hayyan Haidar said.

The 1960s are widely seen as a golden age. Tourism boomed, much of it from the Arab world. A cultural scene of theatre, poetry, cinema and music flourished. Famous visitors included Brigitte Bardot. The Baalbeck International Festival, set amid ancient ruins in the Bekaa Valley, was in its heyday.

Casino du Liban hosted the Miss Europe beauty pageant in 1964. Water skiers showed off their skills in the bay by Beirut’s Saint George Hotel.

Visitors left with “a misleadingly idyllic picture of the city, deaf to the antagonisms that now rumbled beneath the surface and blind to the dangers that were beginning to gather on the horizon,” Samir Kassir, the late historian and journalist, wrote in his book “Beirut”.

Kassir was assassinated in a car bomb in Beirut in 2005.

For all the glitz and glamour, sectarian politics left many parts of Lebanon marginalised and impoverished, providing fertile ground for the 1975-90 civil war, said Nadya Sbaiti, assistant professor of Middle Eastern Studies at the American University of Beirut.

“The other side of the 1960s is not just Hollywood actors and Baalbeck festivals, but includes guerrilla training in rural parts of the country,” she said.

Lebanon was also buffeted by the aftershocks of Israel’s creation in 1948, which sent some 100,000 Palestinian refugees fleeing over the border.

In 1968, Israeli commandos destroyed a dozen passenger planes at Beirut airport, a response to an attack on an Israeli airliner by a Lebanon-based Palestinian group.

The attack “showed us we are not a state. We are an international playground,” Salim Haidar, serving as an MP, said in an address to parliament at the time. Lebanon had not moved on in a quarter of a century, he said.

“We gathered, Christians and Muslims, around the table of independent Lebanon, distributed by sect. We are still Christians and Muslims … distributed by sect.”

To build a state, necessary steps included the “abolition of political sectarianism, the mother of all problems,” said Haidar, who died in 1980.

TICKING TIME BOMB

Lebanon’s brewing troubles were reflected in its art.

A 1970 play, “Carte Blanche”, portrayed the country as a brothel run by government ministers and ended with the lights off and the sound of a ticking bomb.

Nidal Al Achkar, the co-director, recalls the Beirut of her youth as a vibrant melting pot that never slept.

A pioneer of Lebanese theatre, Achkar graduated in the 1950s from one of a handful of Lebanese schools founded on a secular rather than religious basis, Ahliah, in the city’s former Jewish quarter. Beirut was in the 1960s a city of “little secrets … full of cinemas, full of theatres,” she said.

“Beside people coming from the West, you had people coming from all over the Arab world, from Iraq, from Jordan, from Syria, from Palestine meeting in these cafes, living here, feeling free,” she recalled. “But in our activity as artists … all our plays were pointing to a catastrophe.”

It came in 1975 with the eruption of the civil war that began as a conflict between Christian militias and Palestinian groups allied with Lebanese Muslim factions.

Known as the “two year war”, it was followed by many other conflicts. Some of those were fought among Christian groups and among Muslim groups.

The United States, Russia and Syria were drawn in. Israel invaded twice and occupied Beirut in 1982. Lebanon was splintered. Hundreds of thousands of people were uprooted.

The guns fell silent in 1990 with some 150,000 dead and more than 17,000 people missing.

The Taif peace agreement diluted Maronite power in government. Militia leaders turned in their weapons and took seats in government. Hayyan Haidar, a civil engineer and close aide to Selim Hoss, prime minister at the end of the war, expressed his concern.

“My comment was they are going to become the state and we are on our way out,” he said.

In the post-war period, Rafik al-Hariri took the lead in rebuilding Beirut’s devastated city centre, though many feel its old character was lost in the process, including its traditional souks.

A Saudi-backed billionaire, Hariri was one of the only Lebanese post-war leaders who had not fought in the conflict.

A general amnesty covered all political crimes perpetrated before 1991.

“What happened is they imposed amnesia on us,” said Nayla Hamadeh, president of the Lebanese Association for History. “They meant it. Prime Minister Hariri was one of those who advanced this idea … ‘Let’s forget and move (on)’.”

‘I LOST HOPE’

The Taif agreement called for “national belonging” to be strengthened through new education curricula, including a unified history textbook. Issued in the 1940s, the existing syllabus ends in 1943 with independence.

Attempts to agree a new one failed. The last effort, a decade ago, provoked rows in parliament and street protests.

“They think that they should use history to brainwash students,” Hamadeh said. For the most part, history continues to be learnt at home, on the street and through hearsay.

“This is (promoting) conflict in our society,” she added.

Old faultlines persisted and new ones emerged.

Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims fell out following the 2005 assassination of Hariri. A U.N.-backed tribunal recently convicted a member of the Iran-backed Shi’ite group Hezbollah of conspiring to kill Hariri.

Hezbollah denies any role, but the trial was another reminder of Lebanon’s violent past – the last 15 years have been punctuated by political slayings, a war between Hezbollah and Israel and a brush with civil conflict in 2008.

To some, the civil war never really ended.

Political conflict persists in government even at a time when people are desperate for solutions to the financial crisis and support in the aftermath of the port explosion.

Many feel the victims have not been mourned properly on a national level, reflecting divisions. Some refuse to lose faith in a better Lebanon. For others, the blast was the final straw. Some are leaving or planning to.

“You live between a war and another, and you rebuild and then everything is destroyed and then you rebuild again,” said theatre director Achkar. “That’s why I lost hope.”

(Editing by Mike Collett-White)