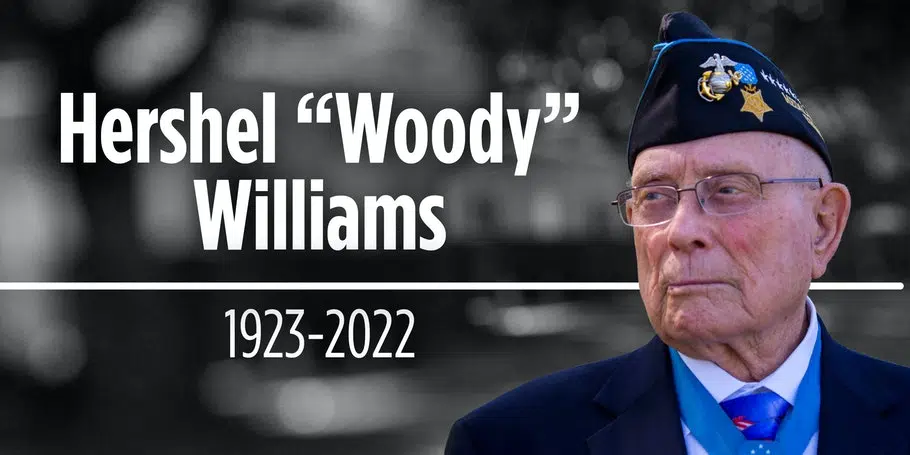

Semper Fi, Woody Williams

Farewell to the last World War II Medal of Honor “caretaker.”

On February 23, 1945, a 21-year-old Marine corporal, Hershel Woodrow “Woody” Williams, watched from the bloody beaches of Iwo Jima1 as our flag was raised atop Mount Suribachi, immortalized by the sculpture at the Marine Corps Memorial2.

For his heroic actions on that same day, Williams became one of 27 Iwo Jima Marines and sailors to receive the Medal of Honor3 — our nation’s highest military award for valor — “For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty…” It was the bloodiest battle in Marine Corps history in which 7,000 Americans perished.

Williams, who was a very humble man and welcomed anyone to address him as “Woody,” was one of 472 World War II recipients of the Medal of Honor. He was the last living WWII recipient until his death this week at age 98 in his beloved home state of West Virginia.

Woody was the youngest of seven children born into a hard-working farming family, and, at just 3.5 pounds at birth in 1923, he was not expected to survive. Thank God he did. He wanted to enlist in the Marine Corps after the “Japs” attacked Pearl Harbor4, but given that his low birth weight hindered his adult stature, he did not meet the 5’6″ minimum height requirement. But the Corps reduced that restriction in 1943 and Woody was in.

He trained in San Diego as an infantryman on the use of flamethrowers. At the time, this weapon was one of the most effective means of extracting Japanese fighters from their cavern entrenchments on Pacific islands. It was a heavy and cumbersome backpack device with three tanks, two for a mixture of diesel fuel and aviation gas and the third for compressed air. And if an enemy bullet pierced the tanks, it meant certain death for its bearer.

His first combat trials were with Company C, 1st Battalion, 21st Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division at Guadalcanal. He then served at the Battle of Guam in 1944 and in 1945 landed on the grainy volcanic sand of Iwo Jima, where he was charged with clearing enemy pill boxes.

Please take a moment to read his full Medal of Honor citation5 and ponder the extraordinary actions of this man. Like all recipients, he was an ordinary individual who demonstrated extraordinary acts of valor when confronted with circumstances that called him to put the lives of others above his own.

After the war, Woody remained with the Marine Corps Reserve’s 25th Infantry Company, and his final rank was Chief Warrant Officer 4. He spent 33 years as a counselor with Veterans Affairs. He was a devoted Christian and served as the chaplain for the Congressional Medal of Honor Society for 35 years. He also headed the Woody Williams Foundation6, supporting the establishment of permanent Gold Star Families Memorial Monuments in communities across our nation and providing Living Legacy scholarships to the children of fallen Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Marines.

Like all recipients, Woody considered himself only a “caretaker” of the medal, and he wore it in honor of all others who served.

The last time we crossed paths was in April of last year at a memorial service for his friend, Charles Coolidge7, the last living WWII European Theater Medal of Honor recipient. They were both proud members of the National Medal of Honor Heritage Center8 in Chattanooga, Tennessee, the birthplace of the medal.

The image that remains seared into my memory is that of Woody standing quietly alone in a private moment over the casket of Mr. Coolidge, saying goodbye. Given his stature, I am reminded of another small man who became a giant among recipients, Desmond Doss9.

In 2020, the Navy christened the USS Hershel “Woody” Williams10 in honor of his service.

The remaining 63 living Medal of Honor recipients issued a statement11, closing with, “Semper Fi and Godspeed, Woody.” Indeed. His wife of 62 years preceded him in death in 2007. He is survived by his two daughters and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Semper Vigilans Fortis Paratus et Fidelis

Pro Deo et Libertate — 1776

reprinted from The Patriot Post – by Mark Alexander

Comments