Below is the letter from Wausau Mayor Doug Diny’s legal counsel addressing the latest charade by the Members of the Wausau Common Council in introducing a resolution seeking approval to spend taxpayer money on yet another frivolous investigation of the mayor.

January 27, 2025

City of Wausau Common Council

To the Members of the Common Council,

I am writing on behalf of my client Mayor Doug Diny. This is a response to the allegations recently lodged against him in the ethics complaint, which alleges he may have broken either the federal laws spelled out in the ethics complaint or otherwise violated the law by temporarily removing the drop box. The short answer is no. The statutes cited in the complaint do not apply (even remotely) to this situation.

For ease of reference and in hopes that this letter will put the matter to rest, the letter has three parts. First, it spells out the indisputable facts and history surrounding absentee ballots and drop boxes; second, it addresses the allegation that the City Attorney’s position provided the definitive answer on the clerk’s absolute authority over the proper use of the drop box; and third, it addresses the specific statutes cited as a basis for federal charges against Diny.

I. The background informing the complaint and where the complaint misses some key points and distinctions.

As way of background, it’s helpful to remember that early in our Nation’s history,

everyone had to go to the polls and vote—in person. That, of course, was hard. People had to travel a long way and sometimes storms or sickness or a war would interfere with

a person’s ability to vote. Conscious that something as precious as voting shouldn’t be needlessly lost, States adopted procedures for what’s called absentee voting.1

1 Andrew C. Scarafile, Note, Regulation or Qualification: The Qualifications Clause, The Elections Clause, and Federal Regulation of Mail-In Ballots, 36 NOTRE DAME J. L. POL’Y & ETHICS 709, 720–21 (2022).

In those instances, the voter applies for an absentee ballot.2 All the same demands of in-person voting still apply, and once those are cleared the municipal clerk can issue the voter an absentee ballot with a return envelope.3 These procedures are regulated both by state and federal law, and the absentee ballots have to be issued by a date in September (45 days before the election), so the ballots can be received by (among others) servicemen and women overseas and returned to the clerk by election day.4 With that in mind, absentee voting has been deemed a privilege, not a right.

Throughout the history of absentee voting, many feared that there was a grave risk of fraud. Even President Carter observed: “Absentee ballots remain the largest source of potential voter fraud.”5 And so myriad procedures sprang up around absentee voting. These procedures included the ballot being sent by U.S. Mail (or delivered in person) to the municipal clerk. As the absentee ballots are returned, they are kept in a separate place by the municipal clerk until they’re opened and placed in a ballot box before being counted on that first Tuesday after the first Monday in November.

At the height of the pandemic, as voters avoided going to a polling place because of COVID-19, there were fears of the Post Offices being overrun with ballots.6 And so, drop boxes were conceived as a plausible solution. From the get-go, they were greeted with controversy. Wisconsin Statutes have little to nothing to say on drop boxes. And a lack of standardization has given rise to concerns about voter fraud and unequal opportunities to vote between different municipalities. Some conservative organizations have even argued that they are illegal.7 And even the non-partisan Legislative Audit Bureau concluded that Wisconsin Elections Commission erred by not promulgating administrative rules regulating drop boxes, instead relying on guidance documents.8

Similarly, the legal history of drop boxes has been a roller coaster. In 2022, the Wisconsin Supreme Court held that drop boxes are illegal.9 Then, just months ago, the State Supreme Court reversed itself in a case called Priorities USA.10 Since then, municipalities have been trying to figure out the answer to various questions—e.g., who authorizes drop boxes and whether a city council can ban drop boxes.11 And they have also wrestled with what are the best practices that a municipality must have for maintaining a drop box. It’s not as simple as just having a box out there for people to drop off ballots.

Rather, municipalities are supposed to (at the very least) make sure that:

- The drop box is secure—no one can tamper with it. That includes being bolted down and sealed.

- Only ballots go into the drop box—they can’t be comingled with other documents and municipal business.

- That there are appropriate procedures for the opening and emptying of the drop box and collecting the ballots.

- That there is proper lighting and video monitoring the drop box.

All of those safeguards are meant to ensure the sanctity of the ballots and our elections.

As the city’s chief executive, after Priorities USA, Diny and the municipal clerk met to discuss placing a drop box in front of City Hall. From the conversation, Diny believed that the issue would be resolved by the Common Council (expressing the will of the voters) and that at the very least any drop box would be secured—not just to the ground but with attendant cameras and sufficient lighting to ensure no one tampered with it.

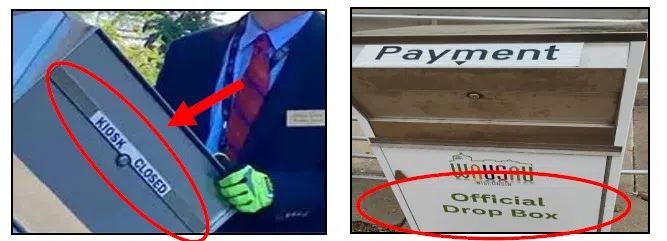

As it has been universally reported, on September 22, Diny arrived at City Hall and found a “drop box” that was not secured, that was not surrounded by lighting and cameras, and that was simply a receptacle for payment. It had no ballots in it. It bore a sticker that said “Kiosk Closed” and it appeared to be locked. In fact, the box itself said nothing about ballots—we added the circles.

2 See id.; Wis. Stat. § 6.86(1)(a).

3 Wis. Stat. § 6.87(4)(b)1.

4 See id. at § 6.34(1) (defining military elector); 52 U.S.C. § 203 (Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act).

5 John R. Lott, Heed Jimmy Carter on the Danger of Mail-in Voting, WALL STREET J., (April 10, 2020).

6 See Will Flanders et al., A Review of the 2020 Election, WIS. INSTITUTE L. & LIBERTY at 32 (2022) (explaining drop boxes were “virtually unknown” prior to 2020).

7 See id.

8 Legislative Audit Bureau, Election Administration (2021),

https://legis.wisconsin.gov/lab/media/rz1nj2dh/21-19full.pdf.

9 Teigen v. Wis. Elections Comm’n, 2022 WI 64 ¶1, 403 Wis. 2d 607.

10 Priorities USA v. Wis. Elections Comm’n, 2024 WI 32, 412 Wis. 2d 594.

11 See, e.g., Evan Casey, 2 Waukesha County Communities Vote to Ban Ballot Drop Boxes, Wis. Pub. Radio (Aug. 26, 2024), https://www.wpr.org/news/waukesha-county-brookfield-new-berlin-vote-ban-ballot-dropboxes.

As the chief executive, Diny removed the drop box and placed it in his office. He immediately informed the maintenance staff and police chief—stating in polite terms: no need for concern, the drop box is in my office; we will hash out the proper placement and security of the box before it’s operational. Over the course of the next week, the story blew up. Demands were made, offers were extended, and the drop box was eventually returned.

The following Tuesday the issue was put before the Common Council. According to press releases, as the drop box sat in the mayor’s office, the clerk found a different box to operate as a drop box, where people could put their payments for the clerk and (if they wanted) their ballots. And to be very clear, there is a large difference between ballot boxes and drop boxes—that point is spelled out in the attached briefs.

The initial investigation came from the Wisconsin Department of Justice with agents swarming City Hall and then raiding Diny’s home. This was met with an immediate motion to quash the search warrant, noting that there was not probable cause that Diny committed a crime. I’ve attached the briefs. And that initial motion was quickly followed by a second motion challenging the competency of the search warrants. That too is attached. It argued that the investigation did not comply with the law—any investigation of voting crimes needs to originate with a complaint to the Wisconsin Elections Commission. Both challenges are scheduled for a hearing this week. And to date the Wisconsin Elections Commission has not issued notice of a formal complaint being filed. Yet Diny has received this ethics complaint laying out two sets of allegations. First, that he ignored the clear legal advice of the City Attorney; second, that he violated federal law.

II. The Clerk’s authority over drop boxes is not as absolute as the City Attorney’s letter suggest.

There is a somewhat open question about who is supposed to fashion the appropriate safeguards for ensuring the drop boxes’ integrity and who has the authority to implement drop boxes. I have qualified the term “open question” because it’s very clear from the Wisconsin Elections Commission and the Supreme Court’s opinion in Priorities USA that the drop boxes must be secured and there are certain “best practices” that must be followed—if a municipality chose to have drop boxes. This is not a trivial matter and not just anything resembling a box will comply with the law.

Another reason I used the term “somewhat open question” is because the opinion in Priorities USA did not address who is to make the final decision when the clerk is not an elected official. There are, after all, two types of municipal clerks: those elected and those who serve at the pleasure of the mayor.12 In Wausau the mayor is responsible for hiring and firing the municipal clerk; he is the statutorily designated as the municipality’s chief executive officer.13 In contrast, a municipal clerk normally performs mere ministerial duties.14 Such duties include, for example, “attend[ing] the meetings of the [city] council” and “keep[ing] a full record of its proceedings.”15 Any discretionary authority that a clerk may have over an election is exceptional.16 And it does not extend as far as the City Attorney’s letter would suggest—that the Clerk’s authority is absolute, that she is the first and final call on the matter.

Consider it this way: the good people of Wausau could petition for drop boxes. And the Mayor could put forth a resolution saying that he or she wants there to be drop boxes and lay out all the reasons Wausau should have them. And then after doing so, the mayor could put the matter before the Common Council. The Common Council could then vote unanimously to implement drop boxes—setting out specific demands in line with Wisconsin Elections Commission’s memos, the Supreme Court’s opinion in Priorities USA, and the best practices other municipalities have adopted. At that point, the voters, the mayor, and the Common Council have also sought to adopt drop boxes. In the face of such unanimous support, the clerk could not (as a subordinate agent) refuse to have drop boxes—a point that the City Attorney’s letter suggests.

For that matter, the Clerk could also not choose to ignore the safeguards that the Mayor and the Council have set out. That is, the clerk couldn’t just co-opt a cardboard Amazon box, scribble “drop box” on it, and plop it down outside City Hall with no cameras, no lighting, and just let the ballots be mixed with whatever other municipal business people deposited in there. That would be nonsense. The Clerk’s authority is not absolute, but the precise boundaries of it have not been established through litigation.

That brings me back to the ethics complaint and Attorney Jacob’s opinion letter. Reasonable minds can disagree on the breadth of the Clerk’s authority. As outlined above, Wausau’s Clerk is not elected and her authority—let alone discretionary authority—is very limited. She would not have the power to override the Council or the Mayor and she certainly would not have the authority to implement “drop boxes” that do not have the necessary safeguards outlined in Priorities USA and Wisconsin Elections Commission’s guidance over the issue. It is simply not the case that her power is absolute and Attorney Jacobs’s opinion to that effect probably did not contemplate her exercising discretion that contravened the necessary safeguards surrounding the drop box.

III. There is no merit to the accusation that Diny violated federal law when he moved the drop box.

That leaves the second point of controversy alleged in the complaint: whether Diny’s conduct constituted a crime. It certainly didn’t violate Wisconsin law—the briefs speak to that. When it comes to federal law, the complaint cites three different statutes as a basis for criminal liability: 18 U.S.C. § 242, 18 U.S.C. § 595, and 52 U.S.C. § 10307(a). There is no discussion of how those statutes relate to Diny’s conduct, but for the sake of putting this to bed and letting the Council focus on running the city, here is the analysis.

When it comes to § 242, that statute makes it a crime to deprive someone of their constitutional liberties because of their race or color or alienage. Here’s the relevant text:

Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, willfully subjects any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth, Possession, or District to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or to different punishments, pains, or penalties, on account of such person being an alien, or by reason of his color, or race, than are prescribed for the punishment of citizens, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than one year, or both.17 Moving the drop box into Diny’s office was not done to target a certain person (or group of persons) based on their race, color, or alienage. What’s more, absentee voting hadn’t even begun—the drop box was locked. No one was inhibited from exercising his or her right to vote; anyone who wanted to absentee vote could do so through the mail or going inside the Clerk’s Office or just waiting until the next day when a different “drop box” was installed. Put simply, this statute plainly doesn’t apply. When it comes to § 595, that too is inapplicable—on its face. The statute is part of the so-called Hatch Act, which prevents federal administrative employees from campaigning for others to be elected in office. That is, IRS employees can’t go out door-to-door campaigning for candidates.

Here is the statute’s text. Whoever, being a person employed in any administrative position by the United States, or by any department or agency thereof, or by the District of Columbia or any agency or instrumentality thereof, or by any State, Territory, or Possession of the United States, or any political subdivision, 12 Wis. Stat. § 62.09(3)(b); Wausau Code of Ordinance §§ 2.08.010–.030.t. municipality, or agency thereof, or agency of such political subdivision or municipality (including any corporation owned or controlled by any State, Territory, or Possession of the United States or by any such political subdivision, municipality, or agency), in connection with any activity which is financed in whole or in part by loans or grants made by the United States, or any department or agency thereof, uses his official authority for the purpose of interfering with, or affecting, the nomination or the election of any candidate for the office of President, Vice President, Presidential elector, Member of the Senate, Member of the House of Representatives, Delegate from the District of Columbia, or Resident Commissioner, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than one year, or both.18

13 Wis. Stat. § 62.09(8)(a).

14 Wis. Stat. § 62.09(11).

15 Wis. Stat. § 62.09(11)(b).

16 Wis. Stat. § 7.15(1). 17 18 U.S.C § 242

18 18 U.S.C. § 595.

19 52 U.S.C. § 10307(a).

For one, Diny is not employed in a federal administrative position. He is an elected, partisan official. He can campaign for whoever he wants. For another, this statute does not apply in the least to him or this situation of moving a drop box into an office before a single ballot had been placed in it.

When it comes to § 10307(a), that statute is also inapplicable. It is part of the prohibitions against “failing or refusing to permit casting or tabulation of votes.” Diny did not refuse to permit anyone to vote or to count votes. Here is the statute’s text:

No person acting under color of law shall fail or refuse to permit any person to vote who is entitled to vote under any provision of this Act or is otherwise qualified to vote, or willfully fail or refuse to tabulate, count, and report such person’s vote.19

He did not refuse to permit anyone to vote, he moved the drop box before absentee voting even started. And he did not fail or refuse to tabulate or report a person’s vote. Only the clerk could engage in such conduct. In other words, this statute is also plainly not applicable to Diny.

IV. Conclusion

In sum, there is no basis for anyone to argue that Diny acted illegally or unethically. He did not violate any state law, and he certainly hasn’t violated any federal law. And his decision to not follow the City Attorney’s opinion is understandable. It does not speak to either the nuance between elected and appointed clerks and it certainly doesn’t speak to the Mayor’s ability to act (as Wausau’s chief executive) and ensure that the best practices prescribed by the Wisconsin Elections Commission were followed in the installation and maintenance of the drop box. Put differently, this ethics complaint should be dismissed and let the Common Council move on with the important business of running the great city of Wausau.

Sincerely,

Joseph A. Bugni

Wisconsin Bar No. 1062514

jbugni@hurleyburish.com

HURLEY BURISH, S.C.

P.O. Box 1528

Madison, WI 53701-1528

Comments