By Andrew Gray

BRUSSELS (Reuters) – Turkey’s elections on Sunday are a key moment not just for the country itself but also for its European neighbours.

With President Tayyip Erdogan facing his toughest electoral test in two decades, European Union and NATO members are watching to see whether change comes to a country that affects them on issues ranging from security to migration and energy.

Relations between Erdogan and the EU have become highly strained in recent years, as the 27-member bloc cooled on the idea of Ankara becoming a member and condemned crackdowns on human rights, judicial independence and media freedom.

Leading members of NATO, to which Turkey belongs, have expressed alarm at Erdogan’s close relations with Russian President Vladimir Putin and concern that Turkey is being used to circumvent sanctions on Moscow over its war in Ukraine.

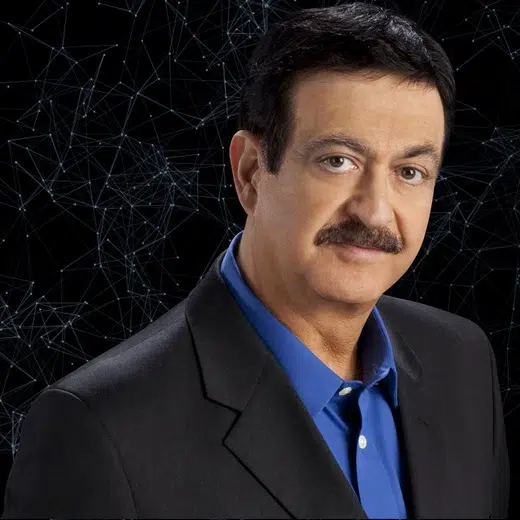

Erdogan’s challenger, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, has pledged more freedom at home and foreign policies hewing closer to the West.

Whatever the outcome, Turkey’s European neighbours will use the election and its aftermath to assess their relationship with Ankara and the degree to which it can be reset.

Here are some key issues that European countries will be watching, according to officials, diplomats and analysts:

ELECTION CONDUCT

EU officials have been careful not to express a preference for a candidate. But they have made clear they will be looking out for vote-rigging, violence or other election interference.

“It is important that the process itself is clean and free,” said Sergey Lagodinsky, a German member of the European Parliament who co-chairs a group of EU and Turkish lawmakers.

Peter Stano, a spokesman for the EU’s diplomatic service, said the bloc expected the vote to be “transparent and inclusive” and in line with democratic standards Turkey has committed to.

A worst-case scenario for both Turkey and the EU would be a contested result – perhaps after a second round – leading the incumbent to launch a crackdown on protests, said Dimitar Bechev, the author of a book on Turkey under Erdogan.

SWEDEN AND NATO

“Five more years of Erdogan means five more years of Turkey being with one weak foot in NATO and one strong foot with Russia,” said Marc Pierini, a former EU ambassador to Turkey who is now a senior fellow at the Carnegie Europe think tank.

Erdogan has vexed other NATO members by buying a Russian S-400 missile defence system and contributing little to NATO’s reinforcement of its eastern flank.

An early test of whether the election winner wants to mend NATO ties will be whether he stops blocking Swedish membership. Erdogan has demanded Stockholm extradite Kurdish militants but Swedish courts have blocked some expulsions.

Analysts and diplomats expect Kilicdaroglu would end the block on Sweden joining NATO, prompting Hungary – the only other holdout – to follow suit. That could let Sweden join in time for a NATO summit in Lithuania in July.

Some analysts and diplomats say Erdogan might also lift his objections after the elections but others are unconvinced.

RELATIONS WITH RUSSIA

Although Erdogan has tried to strike a balance between Moscow and the West, his political relationship with Putin and Turkey’s economic ties to Russia are a source of EU frustration. That will likely continue if Erdogan wins another term.

If Kilicdaroglu triumphs, European officials would likely be content with a gradual shift away from Moscow, recognising that Turkey is in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis and its economy depends on Russia to a significant extent.

“With Russia, a new government will be treading very carefully,” Bechev said.

However, Kilicdaroglu showed this week he was willing to criticise Russia, publicly accusing Moscow of responsibility for fake material on social media ahead of Sunday’s ballot.

RULE OF LAW, CYPRUS

If Kilicdaroglu and his coalition wins, the EU will be keen to see if they keep promises to release Erdogan critics from jail, in line with European Court of Human Rights rulings, and generally improve rule-of-law standards.

“You’re going to have a wait-and-see attitude from the EU,” said Pierini.

If there is a crackdown on graft, European companies may be ready to make big investments in Turkey once again, perhaps with backing from the EU and its member governments, he said.

Efforts to expand an EU-Turkey customs union to include more goods and grant Turks visa-free EU travel could also be revived.

But neither would be easy – not least because of the divided island of Cyprus. Its internationally recognised government, composed of Greek Cypriots, is an EU member, while the breakaway Turkish Cypriot state is recognised only by Ankara.

“This is of course the big stumbling block in our relations,” said European Parliament member Lagodinsky.

However, EU officials see little sign that Kilicdaroglu would change much on Cyprus.

“The big game changer for EU-Turkey relations would be Cyprus. Here the candidates’ agenda, however, does not seem fundamentally different,” said a senior EU official, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Cyprus is one of many factors that make a revival of EU membership negotiations unlikely, officials and analysts say. EU leaders designated Turkey as a candidate to join the bloc in 2004 but the talks ground to a halt years ago.

“There are many other ways to strengthen the relationship, build confidence. There is already a lot of European money that has made its way to Turkey,” said a European diplomat. “I don’t know anyone in Europe who wants to revive EU membership talks.”

(Reporting by Andrew Gray, John Irish and Gabriela Baczynska)