By Sergio Goncalves and Miguel Pereira

SAO VICENTE E VENTOSA, Portugal (Reuters) – Along the main street of Sao Vicente e Ventosa, a quiet village lined with white-washed houses in central-eastern Portugal, there’s a clear winner among the campaign posters jostling for voters’ attention ahead of Sunday’s general election.

The right-wing populist Chega party’s posters are the most numerous and its slogan – “We’ll end corruption and nepotism in Portugal” – is punchier than the vaguer – “More action” – offered on the only poster for the incumbent Socialist party.

São Vicente e Ventosa has become a poster child for Chega after this long-time leftist stronghold of 730 people handed the fast-rising party its highest share of votes in the last election in 2022.

Some 28% of its residents voted for Chega, about four times what the party achieved nationwide.

Since then, Chega has continued to grow, according to opinion polls, proof that the result achieved in this rural parish was no aberration.

It appears to have been an early indicator that Portugal, which only returned to democracy after the fall of a fascist dictatorship 50 years ago, may not be immune to rising populism across Europe, which is expected to result in major gains for far-right parties in European elections in June.

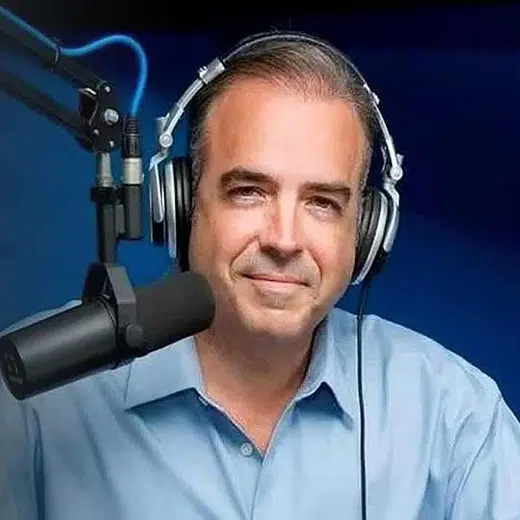

Opinion surveys indicate that Chega, led by charismatic former sports commentator Andre Ventura, could win between 15% and 20% of the vote nationwide to become a kingmaker in a new parliament.

The centre-right Democratic Alliance (AD), led by the mainstream opposition Social Democratic Party (PSD), is seen garnering the most votes but falling short of a parliamentary majority.

Ventura told Reuters last month Chega would demand to be part of a right-wing coalition government in exchange for parliamentary support. AD has so far rejected any type of agreement with Chega.

If AD were to form a minority government, it may not survive long if Chega votes against its first budget later this year.

Chatter in a small cafe in the village frequently focuses on the five-year-old Chega’s growing popularity, with many locals, including opponents, predicting it may, after finishing second in 2022, become the most-voted party this time round.

“From what I’m hearing in the streets, Chega will rise a lot, which is unfortunate and sad,” lamented Joao Martins, 61, who votes Communist. “I don’t understand the mentality of the people, this working-class municipality turning to the extreme right.”

CASTING ITS NET WIDE

Chega, whose name means “enough”, is tapping into discontent with the moderate, mainstream parties that have ruled western Europe’s poorest country for the past five decades.

Part of Chega’s arsenal consists of anti-immigration rhetoric with racist overtones, helping rally ultra-nationalists under its banner, but its broader appeal stems from promises to unseat the traditional parties, stamp out corruption and to ease the ordinary citizen’s tax burden.

Parish Council President Joao Charruadas, 38, a Socialist, said Chega’s voters were typically men aged 30 years to 50 years with low-income jobs. But young people were also supporting the party in growing numbers, drawn in by its smart use of social media, he said.

“It’s a vote against the central government because this parish is not racist, it is not xenophobic,” he told Reuters.

Low average monthly salaries of around 1,000 euros ($1,085), rising prices and lack of public investment in infrastructure were key reasons why many locals, including those who used to vote for left-wing parties, are “giving a big boost to the far right”, he said.

Similar issues trouble millions of Portuguese, making them potential Chega voters.

Founded in 2019 by dissidents from the centre-right Social Democratic Party, Chega has allied with Europe’s hard-right, anti-immigration parties, such as Marine le Pen’s Rassemblement National in France or Germany’s AfD.

However, unlike in many western European countries, tapping into anti-immigration sentiment is unlikely to be a big driver for Chega in Portugal.

EU data show Portugal had the European Union’s second-lowest ratio of immigrants per 1,000 people in 2021. At 4.9, it was less than half that in Germany, the Netherlands or neighbouring Spain.

“Ventura…is a populist guy in the sense that he mixes themes that can be left-wing or right-wing flags,” said political scientist Adelino Maltez.

So, while calling to end the “open doors” immigration policy, Ventura also promises higher pensions and more taxes for banks and oil companies, demands usually associated with the hard-left parties.

“ACT OF REVOLT”

Chega has capitalised on high-profile corruption investigations that led to the resignation of Socialist Prime Minister Antonio Costa in November and toppled a centre-right regional government on the island of Madeira in January.

The investigations are ongoing and no crimes have been proven, while officials denied any wrongdoing.

Still, many find Chega’s anti-corruption promises enticing.

“People are getting angry with the same system. We have more and more banditry and corruption in our country,” said 35-year-old local minimarket owner Mario Goncalves, who plans to vote for Chega. “It’s an act of revolt.”

($1 = 0.9219 euros)

(Reporting by Sergio Goncaleves and Miguel Pereira; writing by Andrei Khalip; editing by Charlie Devereux and Sharon Singleton)

Comments